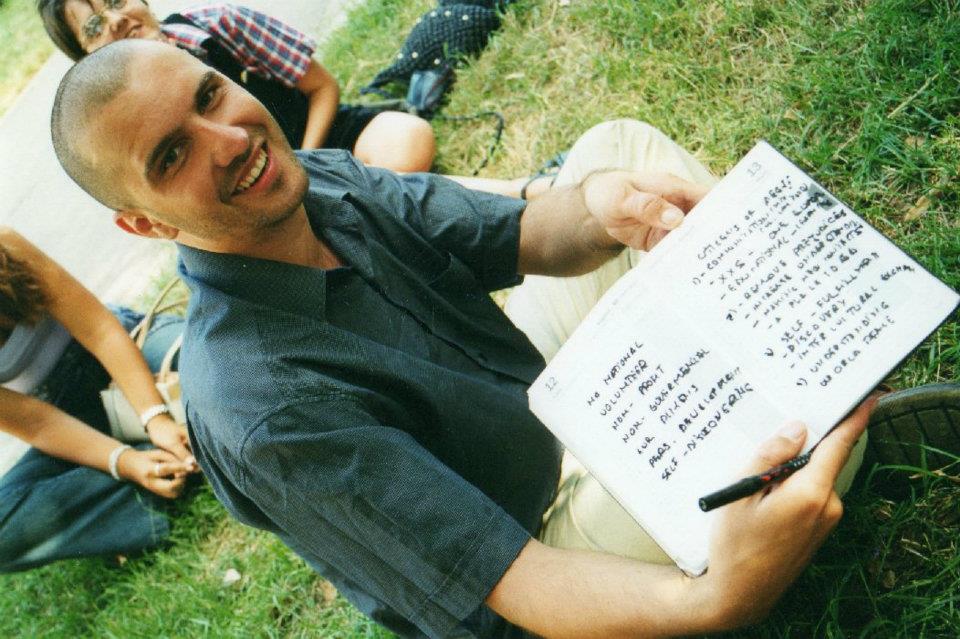

Have you ever wondered how it is to work inside a government? Whether you could actually make a change? This is what happened to Andrei Popescu. The charismatic former NetCom speaker, President of AEGEE-Bucuresti and Agora organiser in 2003 suddenly became Deputy Youth Minister in Romania in December 2015. “Two collaborators of mine came up with the idea that I should be the Minister of Youth and Sports”, Andrei recalls. “They started a campaign and a petition signed by almost 2000 people and more than 100 youth organizations. It did not work out as a minister but at the beginning of December I was being appointed secretary of state.” His term lasted 404 days, until 17th of January 2017, when the current government took over. In the Golden Times Andrei looks back at this eventful period.

GT: Andrei, how was your experience as deputy minister in Romania?

Andrei Popescu: Do you know that feeling when you just finished something that is so great to have as an experience, however not something that you would like to do it again? Pretty much that was the feeling when I left in January.

GT: How come?

Andrei: It was hard. Very hard. But totally worth it. The best and most accelerated learning experience ever. I was jumping in a structure with an organizational culture that is pretty much based on everything you have been fighting before, backed by only two support points: first, your team of councillors that come and go with you and second the experience gained in the youth sector – not bad to have when dealing with youth policies and youth affairs. Plus that childish innocence that let you believe that it can be done despite all the “good advice” – albeit sometimes very honest – given to you that things should be done slower, and, to be fair, should not be done at all.

GT: Sounds like a real culture shock…

Andrei: It often felt like two worlds colliding. On one hand you have the “system” based on ancient rules protected fiercely by some old guardians with one principle: it cannot and should not be done. After all, the best way to preserve this system is to do nothing at all while, God forbid, something might change. On the other hand you have a vibrant sector consisting of young people that cannot wait much longer while, well, they will not be young for much longer and they have pressing needs now – varying from access to education and social inclusion to access to labour market and all types of emergent needs.

Than you have the people at the centre and those working in the ministry all over the country with youth and students centres that are collapsing due to the lack of funding in the youth infrastructure. All of them unmotivated due to the lowest wages in the public administration.

Last but not least you have a ministry where you need to compete with the focus and public funding of sports. That takes the lion part – pretty much around 90% of the ministerial budget.

GT: It’s sad that the youth aspect played such a little role.

Andrei: Do not get me wrong, I am not sorry at all for doing it, actually I am very proud of what happened in this year and a bit. I discovered some wonderful people in the “system” as well, who are doing their best to keep it together and make it work as good as it can. And together we did amazing things like revising the whole youth policy, including youth law, national strategy and public policy for supporting the young people through the youth infrastructure; or like building up a network of youth workers and a support system for youth organizations. And it is worth it even more just because it was hard to do it.

GT: What did you personally learn in terms of skills or knowledge?

Andrei: I do not know what should I start with.

- Patience. Loads of it in different forms from listening to everybody to holding my horses when I wanted something to be done faster or better – pretty much most of the time.

- Spotting the bullshit. It is one of the most important skills when a lot of people are either trying to sell something that is not quite what is should be or holding relevant information back that could change your decision. First I sucked in it, then I got a bit better, but I still do. Thanks God I had reliable people around with a much more sensitive nose than mine.

- Networking. It took me around four months to understand what buttons I should push and to whom I should talk in order to move one thing or another. The paradox is that the Ministry of Youth and Sports should develop, implement and monitor policies addressed to more than a quarter of the Romanian population but it is one of the Ministries with the lowest profile.

GT: What else did you learn?

Andrei: Tolerance to ambiguity. I heard the term before, I thought that I understood it but only here I had the chance to truly test it. As odd as it may be, I did not discover its real meaning in an international environment, but in the Ministry of Youth and Sports. I often found myself facilitating various conflicts among different stakeholders and realized that I could understand and fully support sometimes conflicting points of view. That was very helpful to convince them to stay sometimes at the same table and reach and agreement.

There were many other. Last but not least I would like to mention one of the best life skills I acquired by chance: driving! Low profile ministry normally comes with low budget and missing positions. As a result I had no driver. That was a bit scary while I had not been driving for the last 20 years, not to mention funny for a lot of my colleagues when they saw the beginners sign in the window. This proved to be a blessing in disguise, it offered a freedom and independence to move like few other dignitaries. One year and twenty seven thousand kilometres later I had the chance to go all over Romania and talk with people in the system that no-one from the central body talked to and see the reality first hand in youth or students centres, local representative bodies of the ministry or youth camps.

GT: So you got the feeling that you could move things ahead, to make a change?

Andrei: Definitely! However, mind you, I am highly subjective here. And it depends on the reference point. Moving something in an unmovable public system, even an inch forward, that could actually be the change. Three examples I would like to refer are:

- First, opening to the public debate the provisions of the Youth Law by going around the country, having eight regional consultation meetings gathering more than 400 youth workers and youth organizations or young people in less than a month, negotiating it fiercely with 11 other ministries, especially with the Ministry of Finance

- Second, tineRETEA – youthNET – consisting of 120 youth workers that translated “structured dialogue” in common language by organizing 121 youth consultation and training events all over the country engaging more than 3000 young people.

- Third, launching the NoHate Speech campaign in Romania, which was initiated and coordinated by the Council of Europe at international level. It grew-up nicely and now it is a stand alone process with several youth NGO that are organizing periodically NoHate events.

GT: Awesome!

Andrei: Two more examples, this time attitude changing related:

- First, “It cannot be done”, “It is impossible” and other variations were the most common phrases I heard from my colleagues in the Ministry when I started. Remember I mentioned “patience” as a skill? Well, here is where I tested it the most while these phases were followed by me and my team with a very candid “Why”, starting a time-consuming battle with a lot of procedural and legal arguments that most of the time proved either obsolete, based on the wrong assumptions or simply not relevant to the case. I was filled with joy several months later when I heard these phases replaced with “Well… it is difficult to do it, but it can be done”.

- Second, creating frameworks aiming to put in the same place representatives from the ministry with representatives from youth organizations and youth workers. Two parallel worlds clashing based on conflicting realities. It was a hard lesson for both parties, but an effective one.

GT: Politics is seen as a field where many compromises need to be made. This is often seen as frustrating. How was your experience in this regard?

Andrei: To be frank I am not sure to be the right person answering this question. I held indeed a political position, but I have never seen myself as a politician. The only thing that I cared about was youth policy – and in this regard I was rather straightforward to what I want or how I want it. Sometimes I won, sometimes I lost by clinging to this position.

GT: How long were you in government altogether? From when to when?

Andrei: 1 year, 1 month, 1 week and 1 day precisely! From the 9th of December 2015 until 17th of January 2017.

GT: How did it happen that you were appointed in first place?

Andrei: In November 2015 the government in seat resigned after a national outcry following a tragic fire in the club Colectiv. People blamed the endemic corruption for creating the conditions that led to a tragedy in which 64 people never made it out and many others sustained severe burns. With election due in one year, a technocrat government was asked to step up. Two of the collaborators I used to work with came up with the idea that I should be the new Minister of Youth and Sports. I laughed. How could I work in a ministry that I used to blame for a lot of things? Others around me did not laugh. That made me take this more seriously. They started a campaign and a petition signed by almost 2000 people and more than 100 youth organizations. Some wrote letters to the president and the designated prime minister. It did not work out to make me minister, but at the beginning of December I was being appointed secretary of state, which is the deputy minister in Romanian administration.

GT: That’s an unbelievable story…

Andrei (smiles): I must admit that I never quite believed it to become true until it actually happened. All of that because some people believed in me despite all odds. So… it is basically their fault…

GT: How do we have to imagine an average day in your government life?

Andrei: Well… you must have a lot of imagination. Because there is no such thing as “average life”. There were days when I left at five in the morning on the road to get to the destination late in the evening. Driving “MTSica” – the name I gave my car – served me well and took me all over the country. On the way I used to stop by and visited some colleagues in their territory, or some youth camps. That helped me understand the real needs of the sector. There were days when I was stuck in the office with one meeting after another. There were days when all we did was writing documents, giving feedback on other documents or preparing for important positions. There were days when I was out for events that we organized or other requested my presence and the position of the ministry. And there were many days when it was a bit of each and even more.

GT: What were you doing before being in politics?

Andrei: Twenty years ago I started working as a volunteer. Initially in local activities, soon after that I was involved at national and European level. One year later I had my first attempts of trainings. Some successful, some important learning lessons for future successful events. My dream was to be employed in an NGO. It never happened. On the contrary, in the following year I found myself in the peculiar situation of working for “the other part”, being hired in the National Agency dealing with what was called Socrates programme at the time and Erasmus+ now. For seven years I lived a double life, professionally speaking. During working hours I was Grundtvig assistant manager and in the spare time volunteer, trainer or debate coach in various youth NGOs.

2006 came with a different challenge by taking the coordination of the Youth in Action programme in Romania. My dream to be employed in an NGO never became reality but it was so much better, having now the backing of both aims and programme funding to support the youth NGOs. It took my team more than one year to rebuild the trust in the programme after being suspended for several months. Besides the daily administrative business we built a strong support structure until 2013, involving a training system with a pool of trainers going all over the country, an online platform for non-formal learning and peer learning communities for youth leaders, coaches and mentors.

GT: What are you doing right now?

Andrei: After the Ministry adventure I decided that it is time for another one. Therefore now I am a self-employed free lancer delivering training courses and facilitating events. As we speak I am in a plane taking me to Porto for an international event aiming to build social inclusion projects for young people. Next week I will be in Sibiu for another training dedicated to international volunteers that are now located in Romania. Then… probably a break.

GT: After your government’s term finished, Romania seems to have fallen back in old patterns. The main party in government fights the DNA corruption fighters of Romania and with a couple of legal changes they also wanted to bring sentenced politicians back in power. How could this happen?

Andrei: Democracy is a tricky thing, is it not? Of course people want better politicians and functioning democracy. However, sometimes they get fed up. And when they get tired they do not show up to vote. Less than 40% of the citizens showed up in December at the last election. “If you think democracy is expensive, try to see how much the lack of it costs!”, said once Churchill. And now we pay the bill.

GT: Don’t people want better politicians and a truly functioning democracy?

Andrei: Truth being said, the election campaign was virtually non-existent and consisted more in attacking the adversary rather than coming up with policies and ideas. Truth being said, many people do not care about ideas and do not take the time to analyse them. Truth being said, the parties that are now in the opposition did not come with an alternative that was credible. So… a lethal combination in which we all should take responsibility. Including the present Government as well as the previous one in which I was part.

GT: Tenthousands of people have been demonstrating against your successors, the current government in the past couple of months. How successful is the fight?

Andrei: Yes, indeed, many people reacted when a governmental bill was proposed. This bill basically proposed to erase penalties for several crimes including corruption-related ones. Ten days later and several hundred thousand people in the streets the bill was withdrawn. So yes, you may say that this was successful. However this is just an important “battle” but not the “war” against corruption that will continue for a long time. I believe in a more important and truly successful interesting side effect of the anti-corruption protests in Romania: the awareness that they entered in the public mentality as a peaceful form of pressuring the authorities. It is impressive considering that the protests took place for more than one month with number of citizens varying from few thousands to a peak of more than half a million citizens in 40 different cities.

GT: Were you on the streets, too?

Andrei: Of course. For the five days I was in the street together with a group of drummers we shouted exclusively NoHate messages. There were groups of protesters coming to our group asking us to support them in sending some of their messages. If they implied hate or stereotyping we respectfully but firmly declined to support them. It was amazing to see their reaction. With one exception everyone else accepted immediately our right to refuse to support them and a lot of them actually joined us! During the protests I posted several NoHate messages on my Facebook page with topics varying from how to behave during a protest in order to keep it peaceful and non-violent to warnings related to messages that might put an anathema over an entire group of people – and the importance to focus on what matters and brings us together, not on what divide us.

GT: How can Romania become more democratic? Do you need better politicians? Is a change of mindset of the population necessary so that they don’t just follow the party with the biggest promises?

Andrei: Yes to the politicians. Yes to the mindset changing. And more. Politicians are, after all, mirroring the society. Like it or not. So if we want responsible politicians we need to equally take responsibility as citizens. Protesting makes a lot of sense. But it is it ultimately a tool after using all the others. The fundament is to show up to vote and actually vote informed. Then following are the acts of the politicians, being actively involved in debates, proposing solutions, signing petitions when needed… in short: being involved in the community for real. And we should not only look to the Parliament, but start with the local politicians that are easier to reach and normally have the power to affect our daily life more for better or worse. We should be critical, but informed and balanced.

GT: What can young people do? How can they contribute to the necessary change?

Andrei: The problems of young people are not fundamentally different than the problems of the society. However, they feel the burden more acute in many cases. Therefore I think that you people need to do exactly what is expected to be done by any citizen. Plus, to volunteer more and get more involved in youth activities and non-formal learning.

GT: Anything you would like to add?

Andrei: Thank you for this opportunity. AEGEE was truly a school of life for me and helped me understand the world better. Going international was not just something kool to do, but the right thing to understand and respect those around me.